KernelBench: Can LLMs Write GPU Kernels?

TL;DR

We introduce KernelBench, a benchmark designed to evaluate the ability of large language models (LLMs) to generate efficient GPU kernels for optimizing neural network performance. With 250 well-defined neural network tasks spanning foundational operators, simple fusion patterns, and full ML architectures, the benchmark tasks LLMs to replace PyTorch implementations with custom kernels that are correct and performant. KernelBench highlights the potential for agentic optimization for computer systems with dense feedback signal, where systems iteratively refine kernel designs using profiling tools and tight feedback loops to achieve near-peak hardware utilization. As models scale, well-optimized kernels have far-reaching implications, from reducing the massive energy demands of AI systems to enabling fair and efficient comparisons of novel architectures. By providing aspirational tasks and focusing on agentic approaches, KernelBench envisions a future where LLMs can autonomously drive innovation in GPU programming and ML system optimization.

- Huggingface Dataset: https://huggingface.co/datasets/ScalingIntelligence/KernelBench

- Github Repo: https://github.com/ScalingIntelligence/KernelBench

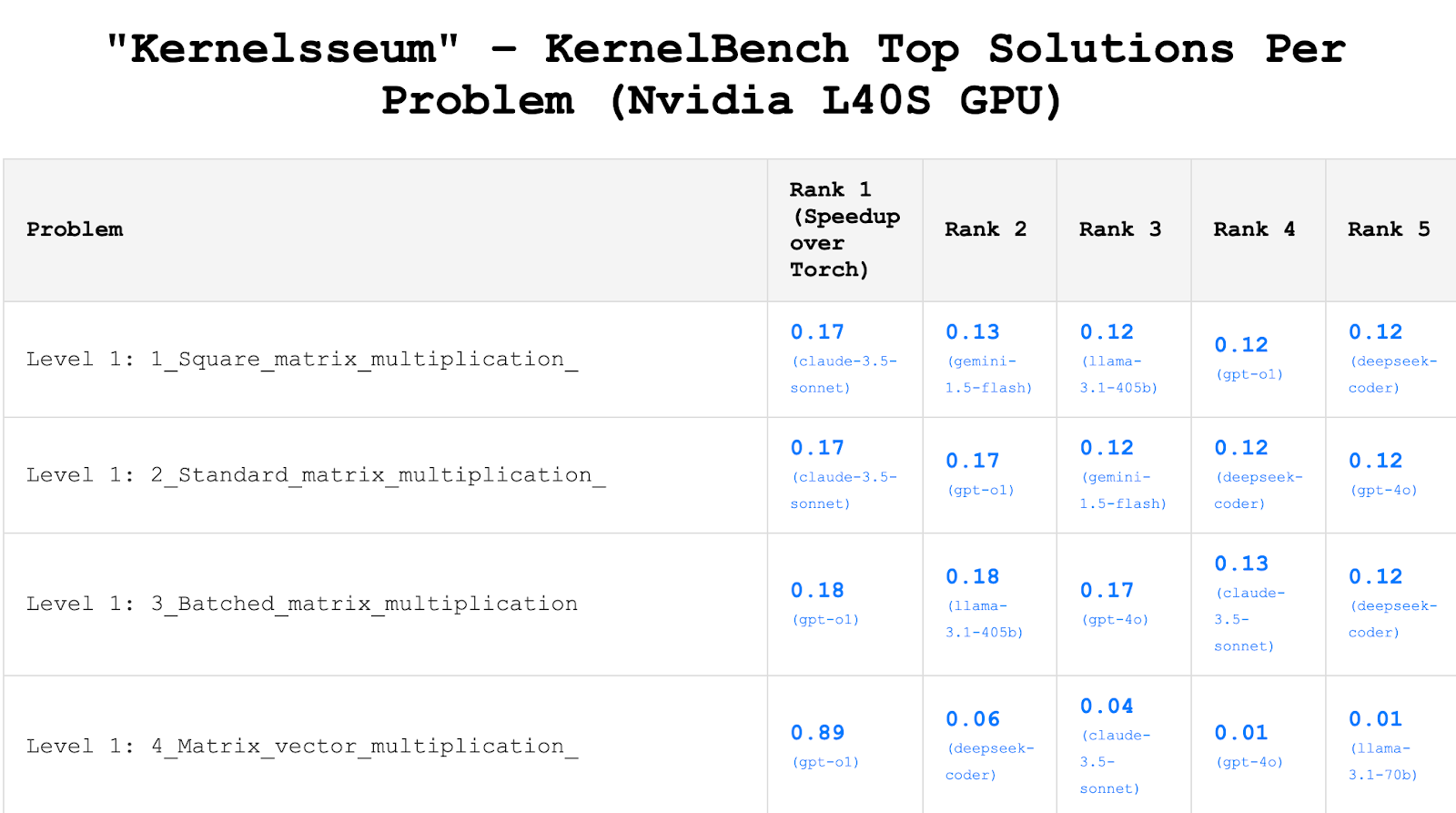

- “Kernelsseum”: A Leaderboard for Top Solutions Per Problem: https://scalingintelligence.stanford.edu/KernelBenchLeaderboard/

Kernels are the kernel of deep learning.

…but writing kernels sucks.

Consider a machine learning researcher with a promising new attention mechanism that could improve LLM efficiency by 30%. To actually test out this idea, they need to:

- Write a prototype in PyTorch (okay, not too bad)

- Profile it and discover it’s 5x slower than normal attention

- Spend weeks writing GPU kernels to make it fast

- Debug weird edge cases and numerical instabilities

- ….???

In an ideal world, you could:

- Write your PyTorch code

- Push a button and go get lunch

- Return, and look through the blazing-fast kernel implementation your LLM wrote for you. This kernel handles edge cases, is numerically stable, and runs at near-peak hardware utilization.

This future (hopefully) isn’t science fiction: we think it’s possible. To measure progress, we’re introducing KernelBench, a dataset of 250 well-defined neural network operations with reference implementations given in Pytorch. KernelBench measures the ability of LLMs to write custom GPU kernels that implement and accelerate these operations. Beyond the 250 core tasks in KernelBench, we also introduce 20 aspirational tasks from HuggingFace models to benchmark the ability of LLM systems in not only just writing GPU kernels but also working on integrating GPU code optimizations in a software library setting.

Why Are Kernels Important?

As models grow larger and become more embedded into our daily lives, having fine-grained control over hardware resources to extract the most performance out of GPUs directly translates to significant energy and cost reductions. For example, ChatGPT alone is estimated to consume over half a million kilowatt-hours daily — roughly equivalent to the power usage of 180,000 U.S. households. At this scale, a 5% speedup isn’t just a number on a benchmark, it’s real energy and money saved. Beyond savings, optimized GPU kernels also allow machine learning researchers to fairly evaluate and compare new model architectures, and efficiency often means unlocking new capabilities that push the field of AI forward.

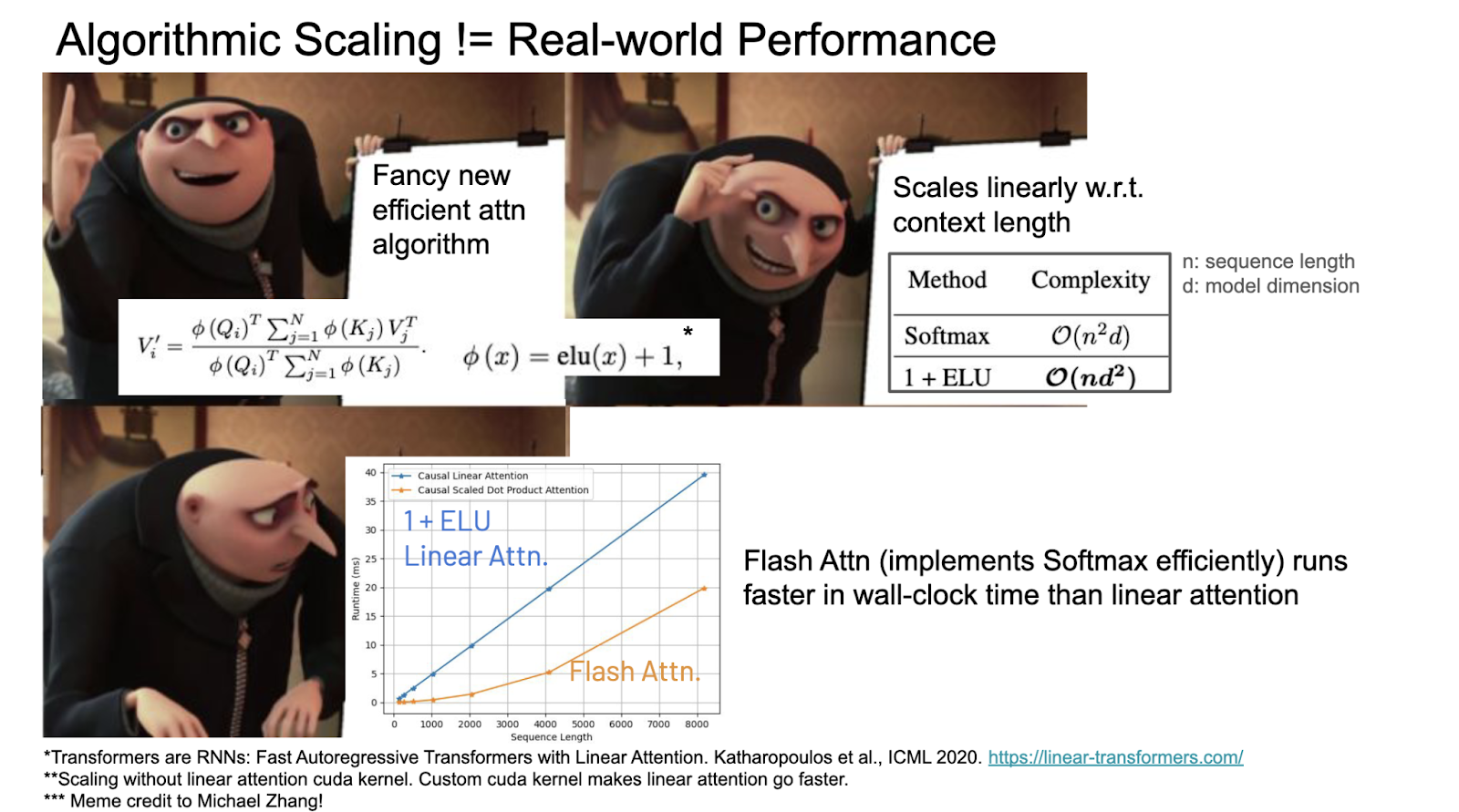

Big O is not all you need.

In algorithm classes we are taught to view Big O as the gold standard for measuring the efficiency of algorithms. In ML research, new model architectures may have better theoretical complexity, implying they should outperform traditional architectures in speed or efficiency, but when it comes down to real-world performance, these newer models can struggle to keep up with established architectures.

(Meme credit to Michael Zhang)

Why doesn’t Big O analysis match actual performance?

Established architectures benefit from years of optimization in their underlying kernels. These kernels are tailored to run efficiently on specific hardware, exploiting all the features of the hardware to maximize performance. On the flip side, newer models often lack this level of optimization and lack adequate hardware utilization, which can result in disappointing performance despite their appealing theoretical claims.

Optimized GPU kernels are important for designing ML architectures. The lack of well-written GPU kernels makes it difficult to do apples-to-apples model architecture comparisons given a fixed compute budget and a fixed hardware platform, so we cannot effectively determine the effectiveness of an architecture. Consider the following example scenarios:

- Scenario 1: an asymptotically good and hardware-aware architecture might be overlooked due to the lack of efficient implementations

- Scenario 2: two architectures that are asymptotically similar, but one is hardware-aware and the other is not. Without actual implementations they might look similar on paper, but in practice one will run much faster than the other.

- Scenario 3: architecture A is asymptotically better than architecture B, but architecture B is hardware aware. Without good implementations for both, it’s unclear which one is faster in wallclock time…….

Can we use LLMs to generate correct and performant GPU kernels?

Unlike many other coding tasks, writing efficient GPU kernels is challenging due to the need for parallelization scheme design, memory management, and hardware-specific optimizations. GPU programming isn’t just about writing syntactically correct code; it requires a deep understanding of GPU architecture to ensure that code is both correct (produces the right output) and performant (fully utilizes the GPU’s capabilities). These factors make GPU programming a rich problem for LLMs, as it involves a bigger optimization search space beyond basic syntax or logic generation.

Recent work on inference scaling laws shows that when you have automatic verifiers, throwing more compute at generation can dramatically improve success rates. Our lab’s recent work (Large Language Monkeys) showed that with coding tasks, going from 1 to 250 samples boosted the solve rate from 15.9% to 56% on SWE-Bench Lite with DeepSeek-Coder-V2-Instruct. GPU programming is a task with strong verification mechanisms and clear feedback signals. For correctness, ground truth is determined by running the generated code on random inputs and comparing the outputs with those of the baseline to check if they match. Performance is measured as the wallclock time and comparing speedup over the reference baseline.

GPU programming is also great for agentic and RL approaches, as the system can iteratively refine kernel designs with reliable, measurable outcomes. Profiling tools like NVIDIA’s Nsight Compute (NCU) provide in-depth feedback on performance bottlenecks, memory usage, and thread utilization, which gives the agent a lot of data to adjust optimizations and improve efficiency. Together, these qualities create a structured environment and tight feedback loop where an agent has verifiable correctness and performance metrics to iterate toward increasingly optimized and correct kernel code.

KernelBench

We introduce KernelBench, a collection of 250 PyTorch neural network operations that we think systems should be able to automatically write optimized kernels for. KernelBench provides the reference implementation in PyTorch, and the task for an LLM is to replace torch layers with custom implementations. We currently only focus on the forward pass as a first step. The core tasks in KernelBench are divided into three levels, with an additional level 4 of 20 aspirational tasks:

- Level 1 (100 tasks): Single-kernel operators like convolutions, matrix multiplies, and layer normalization. The foundational building blocks of neural nets.

- Level 2 (100 tasks): Simple fusion patterns (e.g. conv + bias + ReLU). Sure, you could run three kernels, but one fast kernel is way better.

- Level 3 (50 tasks): Full ML architectures (e.g. MobileNet, VGG, MiniGPT). This is the end goal –– intelligent systems that can optimize entire model architectures end-to-end.

- Level 4 (20 additional aspirational tasks): Huggingface architectures that require browsing the HF source code and making changes to the library.

We only provide baseline evaluations for the first three levels. Level 4 is currently a far-reaching aim and we do not provide baseline evaluations for this level; however, we believe that this level could ultimately play a significant role in advancing the capabilities of LLMs to interact with complex, real-world codebases, where they not only assist with code generation but can also drive architectural improvements and optimizations in widely-used frameworks.

The tasks in KernelBench are a mix of written manually, generated by an LLM or script, and collected from Github. All tasks are manually cleaned up and verified. Each problem has a class named Model to denote which torch-based architecture we want optimized. The torch reference implementations are cleaned up to be self-contained in one file, with the modules containing only the init and forward functions (and helper functions called in the init and forward functions). In addition to the torch module, we also provide functions get_inputs() and get_init_inputs() for generating random parameters for the forward pass and the initialization, respectively. The shapes of random inputs for testing are manually chosen. We also modify the architecture manually to eliminate operations such as dropout to make the results deterministic (within a generous tolerance threshold).

- For level 1, a list of operators are manually curated and categorized. Representative examples of various operators (matmul, normal convolutions, pointwise operators, reduction, etc…) are written in torch manually and and used as one-shot examples for LLMs to generate variants; for example, variants of convolution could be having different dimensions (1D, 2D, or 3D), the input and kernel sizes could be symmetric (same in all dimensions) or not, and the convolution could be transposed.

- For level 2, mainloop operators (e.g. matmul, conv, and variants) and epilogue operators (e.g. activations, pointwises, norms, reductions, …) are manually curated. A script is used to randomly pick one mainloop operator and 2 to 5 epilogue operators as a specification. The specification is passed into an LLM along with a one-shot example (a pair of specification and torch code) to generate the torch code.

- Level 3 is a mix of LLM generated well-known ML architectures like AlexNet and real ML architectures collected from Github (MiniGPT). Real ML architectures are cleaned up to only have the init and forward functions.

- Level 4 is generated with a script. Since Huggingface provides a standardized API to call various language models, this level is generated programmatically with a script that swaps out the model names and parameters such as batch size and sequence length.

While the tasks (architecture implementations) are given in Pytorch, KernelBench is language agnostic, allowing the solutions to use any libraries and DSLs (including Triton, ThunderKittens, CUTLASS, …) such that different levels of abstractions for GPU programming can be explored. It is also fully flexible for the LLMs to determine the optimizations to apply (e.g. making decisions such as kernel fusion).

Here’s a simple example of vector addition to illustrate our task format and a CUDA-based solution:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class Model(nn.Module):

def __init__(self) -> None:

super().__init__()

def forward(self, a, b):

return a + b

def get_inputs():

# randomly generate input tensors based on the model architecture

a = torch.randn(1, 128).cuda()

b = torch.randn(1, 128).cuda()

return [a, b]

def get_init_inputs():

# randomly generate tensors required for initialization based on the model architecture

return []

Here’s an example of a CUDA based solution using custom CUDA C++ operators in torch via load_inline(). This entire file is LLM-generated. The custom CUDA code is supplied as a string and JIT compiled. In this example, the torch addition expression for two vectors is swapped out with the custom elementwise_add_kernel.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

from torch.utils.cpp_extension import load_inline

# Define the custom CUDA kernel for element-wise addition

elementwise_add_source = """

#include <torch/extension.h>

#include <cuda_runtime.h>

__global__ void elementwise_add_kernel(const float* a, const float* b, float* out, int size) {

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (idx < size) {

out[idx] = a[idx] + b[idx];

}

}

torch::Tensor elementwise_add_cuda(torch::Tensor a, torch::Tensor b) {

auto size = a.numel();

auto out = torch::zeros_like(a);

const int block_size = 256;

const int num_blocks = (size + block_size - 1) / block_size;

elementwise_add_kernel<<<num_blocks, block_size>>>(a.data_ptr<float>(), b.data_ptr<float>(), out.data_ptr<float>(), size);

return out;

}

"""

elementwise_add_cpp_source = "torch::Tensor elementwise_add_cuda(torch::Tensor a, torch::Tensor b);"

# Compile the inline CUDA code for element-wise addition

elementwise_add = load_inline(

name='elementwise_add',

cpp_sources=elementwise_add_cpp_source,

cuda_sources=elementwise_add_source,

functions=['elementwise_add_cuda'],

verbose=True,

extra_cflags=[''],

extra_ldflags=['']

)

class ModelNew(nn.Module):

def __init__(self) -> None:

super().__init__()

self.elementwise_add = elementwise_add

def forward(self, a, b):

return self.elementwise_add.elementwise_add_cuda(a, b)

Evaluation

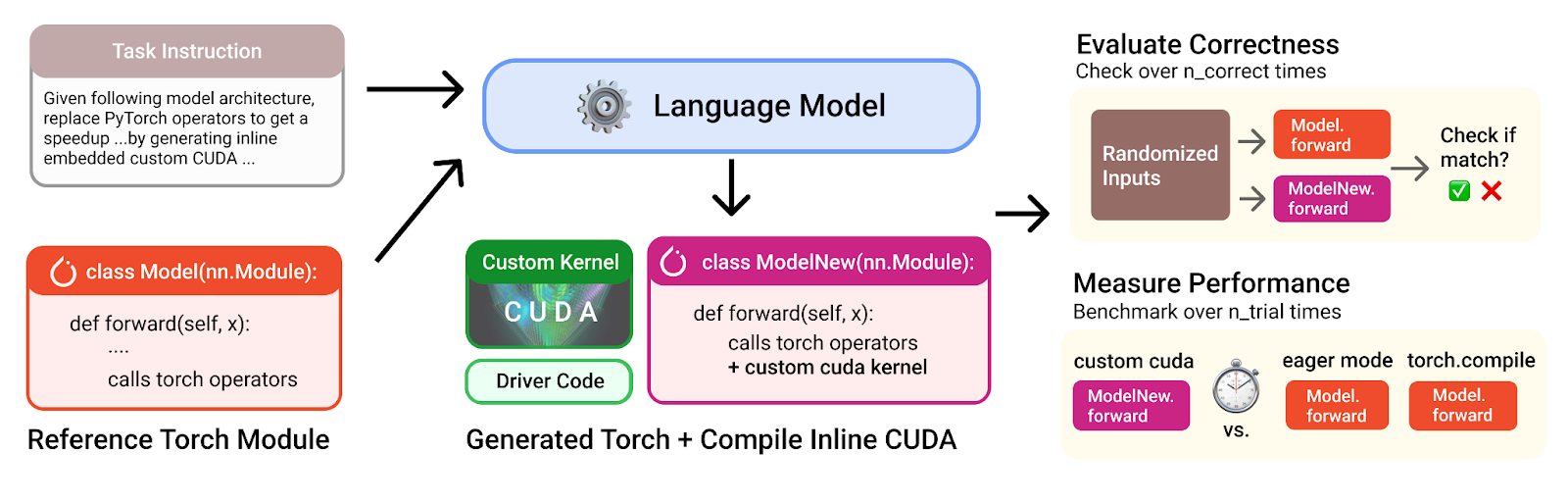

When evaluating GPU kernels, we focus on three criteria with each building upon the previous:

- Compilation: the generated kernel(s) is syntactically valid in the target programming language

- Correctness: the generated kernel(s) can be run without errors and produces the same output as the reference code across a range of inputs

- Performance: speedup of the generated kernel(s) over a reference baseline to determine performance gains, given it is correct

In our context, correctness specifically means, given randomized input values for a predefined set of shapes, the optimized kernel should yield outputs that are numerically equivalent (within an acceptable margin of error, if necessary for floating-point operations) to those produced by the baseline implementation. We choose our numerical equivalent threshold as having absolute and relative tolerances being 1e-02, a generous threshold enabling precision changes and alternative algorithms. A common tradeoff in GPU kernel design is specialization versus generality. Specialized kernels, tuned for particular input shapes or patterns, can often achieve significant performance gains; general-purpose kernels, by contrast, aim for broader compatibility but may sacrifice peak performance. For our purpose, since the aim of our project is to cheaply and quickly generate specialized kernels, we choose to constrain our correctness checks to specified input shapes without requiring broad generalization across all possible shapes. We generate 5 sets of random inputs with fixed shapes, and the kernel is considered to be correct if it produces the numerical equivalent outputs as the unoptimized baseline for all 5 inputs. It is possible to have a stricter measurement of correctness by using more random inputs (the number of correctness trials is a customizable parameter), but we capped it at 5 due to evaluation speed.

Caption: Illustration of KernelBench design

In KernelBench, we made the decision not to provide a predefined train/validation/test set split; however, users are welcome to create their own splits based on their specific needs and goals. Our benchmark doesn’t include additional information to distinguish between training and testing examples, as the focus is on real-world challenges that demand open-ended, high-performance solutions—writing custom GPU kernels and optimizing them to their absolute limits (you’re only constrained by the speed of light!). These tasks, which revolve around foundational operators for machine learning, are designed to have a meaningful impact. Improving these kernels, in any way, can potentially lead to substantial real-world benefits.

Initial Evaluation

Baseline Greedy Evaluation

We evaluate the 250 problems from Levels 1 to 3 from KernelBench on various frontier models, with greedy decoding parameters (temperature = 0).

Compilation and Correctness

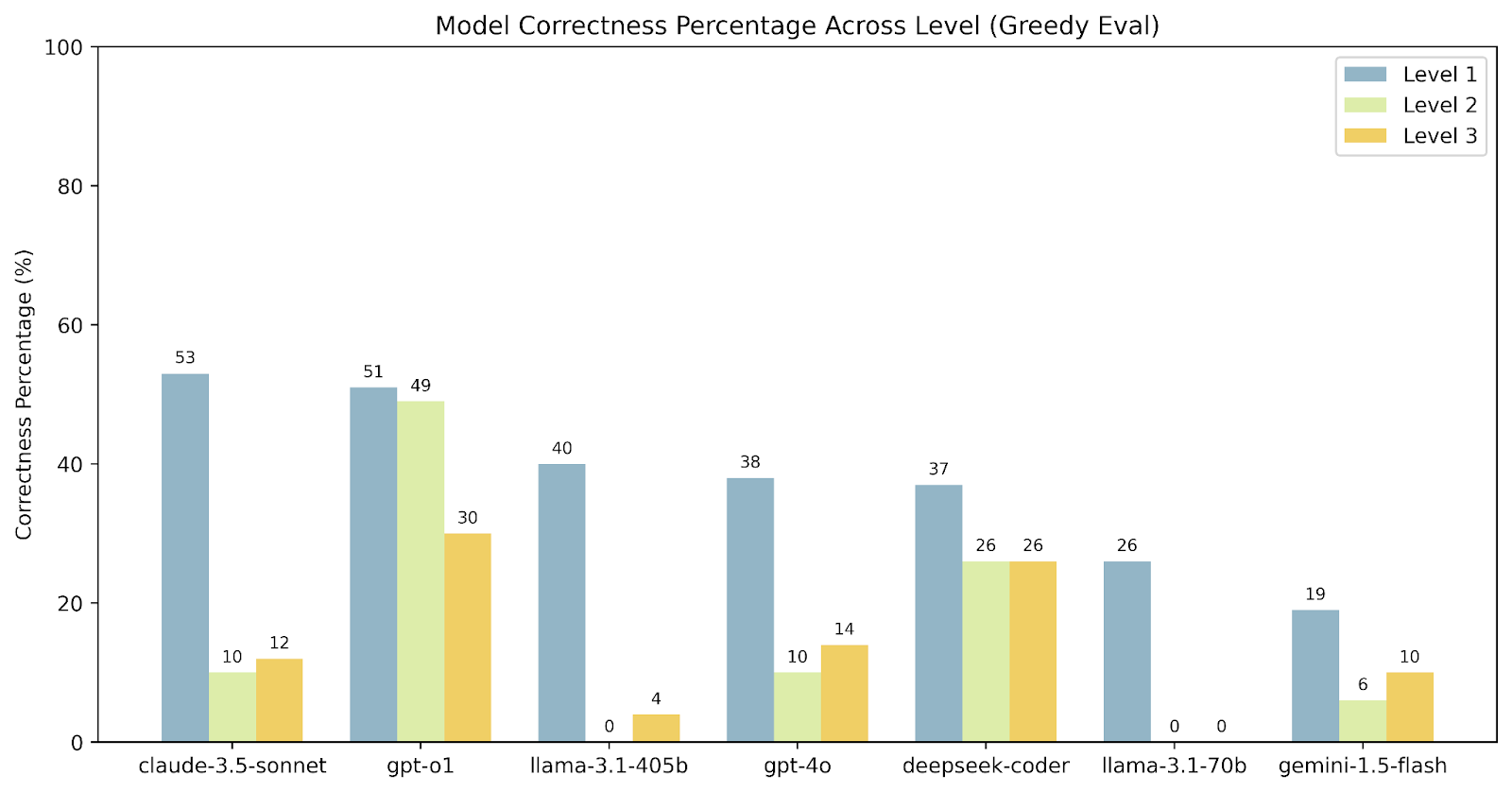

Across the 3 levels of the problems, most models do generate compilable CUDA code. However, maintaining correctness (same output as torch reference code) becomes increasingly challenging as the reference torch code gets more complex (simple operators in level 1 to fused operators in level 2 to whole model architecture in level 3).

Comparing across various models, we note while some models do well on Level 1 tasks, correctness quickly drops off for Level 2 and 3 tasks. Larger models of the same family also seem to get more correct solutions. It is also particularly interesting that the o1 model does significantly better than gpt-4o on correctness for more challenging Level 2 and Level 3 problems, highlighting scaling inference time compute might have played a role here.

Caption: Percent of Correct Samples across 3 Levels of problems across models

Pass@k

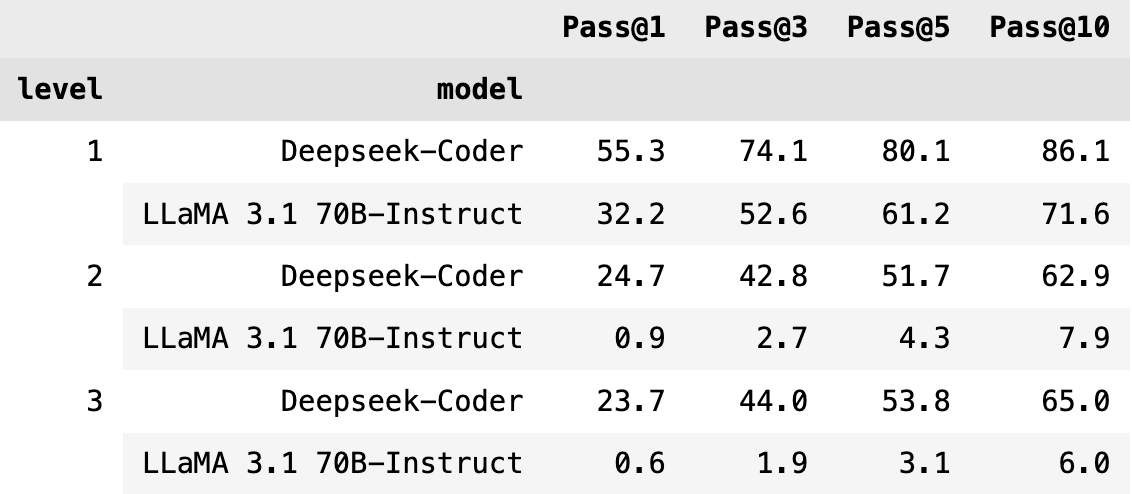

Beyond greedy decoding, we are also interested in pass@k, having at least 1 correct (and successfully compiled) solution given k attempts, as introduced in the HumanEval paper. We sample models with high decoding temperature (deepseek-coder with temp=1.6, and Llama 3.1 70b-Instruct with temp=0.8) for more diverse samples, compute pass@1,3,5,10 with N=100 samples.

Pass@k is defined as \(\text{pass@$k$} := \mathop{\mathbb{E}}_{\text{problems}} \left[ 1 - \frac{\binom{n - c}{k}}{\binom{n}{k}} \right]\) where $n$ is the total number of samples and $c$ is the number of correct samples.

Caption: Pass@k performance for Deepseek-coder and Llama 3.1 70B Instruct

Caption: Pass@k performance for Deepseek-coder and Llama 3.1 70B Instruct

As we increase k, correctness improves, suggesting it might be easier to solve such tasks with more parallel samples (as introduced in the Large Language Monkeys paper). However, we see a stark difference between deepseek and llama 3.1 70b performance, highlighting the importance of base model capability even when conducting inference time scaling.

Tradeoff between Correctness and Performance

We only analyze correctness in the section above. However, in the case of kernel engineering, we care deeply about performance. Looking at the generated kernels, we found there is a tradeoff between correctness and performance, two objectives that are often at odds with each other. Code with more optimization could give better performance gain, but could also risk making more errors and hence likely to fail correctness. Optimizing for performant code while guaranteeing correctness creates a new direction for code generation, while most existing benchmarks and methodologies focus on passing correctness; we are excited to keep exploring that.

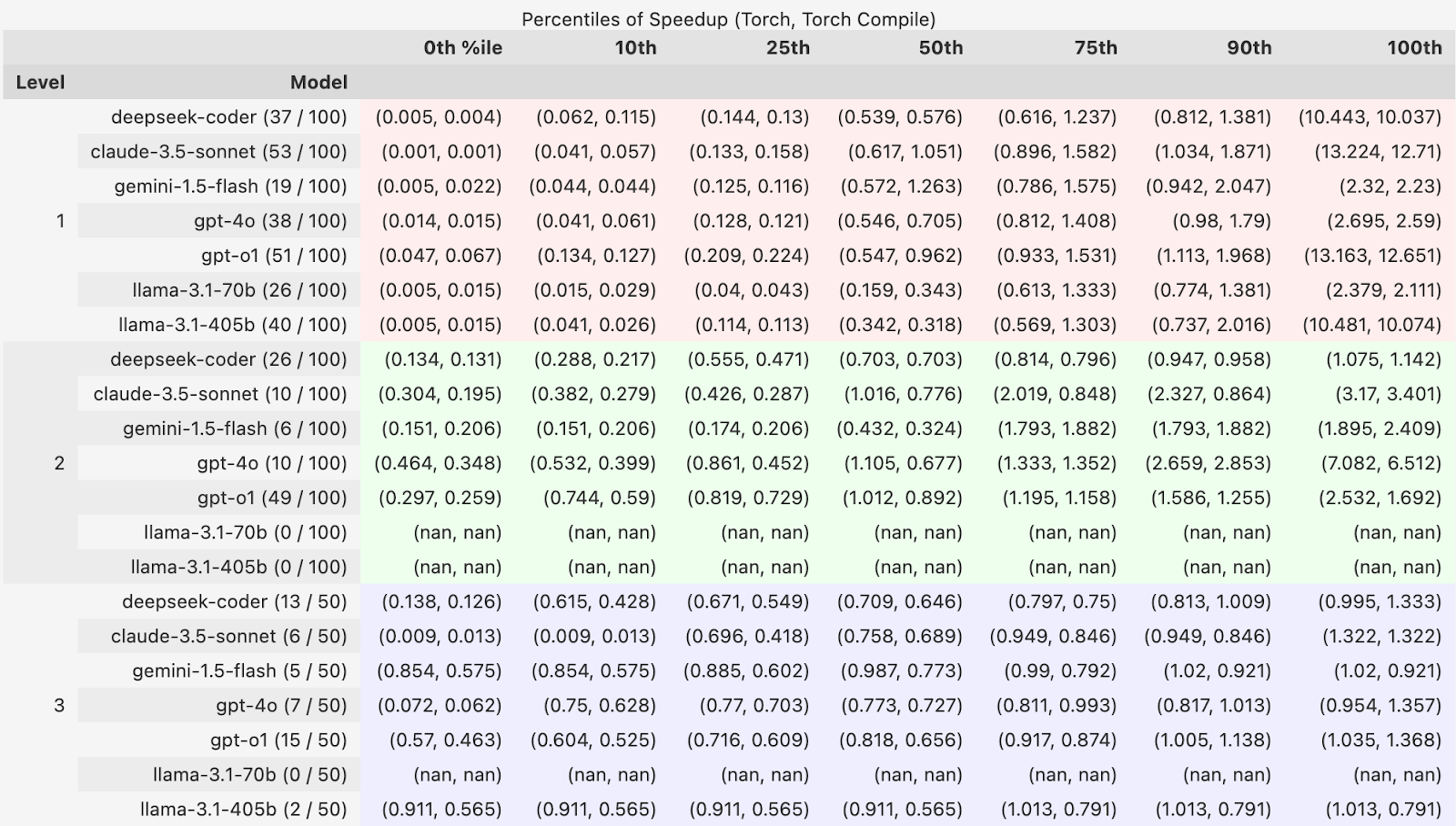

Performance: Percentiles of Speedups

When evaluating performance, we prioritize correctness, as incorrect but fast code is not useful. Therefore, speedups are calculated using only the correct samples. To present a comprehensive view of performance, we report speedups in percentiles. The count of correct samples for each model is indicated in parentheses after the model name in the table below.

In addition to the baseline PyTorch implementation, we also compare speedups against torch.compile() using its default mode. The speedup is defined as \(\frac{t\_baseline}{t\_generated}\)

Caption: Percentile of Speedups vs. Baseline for both Torch and Torch Compile across 3 levels

Among the samples that are correct, we see that most generated kernels exhibit relatively slow speedups over torch and torch.compile baseline, but a few are notably faster as outliers! This piqued our interest and led us to the following investigations.

“Kernelsseum” –– A Per Problem Leaderboard

To better understand the LLM-generated kernels, we also present a leaderboard to inspect the kernels generated by greedy evaluation on KernelBench. This shows the top 5 LLM-generated kernels per problem, and some problems might lack any correct solutions. Note the performance result is hardware-dependent and currently evaluated on the Nvidia L40S GPU.

You can click on entries to see the generated code for each kernel.

Right now, the leaderboard only features solutions generated through greedy evaluation. In the future, we aim to make it an open submission leaderboard to allow contributions from the broader community.

Interesting Kernels

Diagonal Matrix Multiplication

Problem 13 in level 1 involves multiplying a matrix by another diagonal matrix:

torch.diag(A) @ B

torch.diag() takes in a vector of the diagonal elements of a matrix and returns a 2-D square tensor with the elements of input as the diagonal. The result is a matrix-matrix multiplication.

Mathematically, multiplying a matrix by a diagonal matrix is equivalent to scaling each row (or column, if the diagonal matrix is on the right side) of the original matrix by the corresponding diagonal element. As a result, the diagonal matrix doesn’t need to be explicitly constructed, reducing both memory usage and computational overhead.

This is the problem that gets the >12x speedup over torch and torch.compile() in level 1 for multiple models, one example of these generated CUDA kernel is below:

__global__ void diag_matmul_kernel(

const float* diag,

const float* mat,

float* out,

const int N,

const int M) {

const int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

const int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (row < N && col < M) {

out[row * M + col] = diag[row] * mat[row * M + col];

}

}

Kernel Fusion

Problem 14 in level 2 performs a matrix multiplication, division, summation, and then scaling:

x = torch.matmul(x, self.weight.T) # Gemm

x = x / 2 # Divide

x = torch.sum(x, dim=1, keepdim=True) # Sum

x = x * self.scaling_factor # Scaling

There’s a solution generated by claude-3.5-sonnet that has an approximately 3x speed up over both torch and torch compile:

// Fused kernel for matmul + divide + sum + scale

__global__ void fused_ops_kernel(

const float* input,

const float* weight,

float* output,

const float scaling_factor,

const int batch_size,

const int input_size,

const int hidden_size

) {

// Each thread handles one element in the batch

const int batch_idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (batch_idx < batch_size) {

float sum = 0.0f;

// Compute matmul and divide for this batch element

for(int h = 0; h < hidden_size; h++) {

float elem = 0.0f;

for(int i = 0; i < input_size; i++) {

elem += input[batch_idx * input_size + i] *

weight[h * input_size + i];

}

// Divide by 2 as we go

sum += (elem / 2.0f);

}

// Scale and store final result

output[batch_idx] = sum * scaling_factor;

}

}

The solution fuses all four operations into a single GPU kernel, eliminating the overhead of writing intermediate results to memory and reading them back for subsequent operations. Additionally, combining the matrix multiplication with the dimension-wise summation reduces the size of the final output, minimizing memory bandwidth usage.

Next steps and public involvement

In the Scaling Intelligence Lab, we plan to continue extending this work to enable LLMs to write efficient GPU kernels. The initial results show significant room for improvement, and we are optimistic about the potential for significant advancements in future iterations.

There is a lot of interest in the community in GPU programming and LLMs for GPU code generation. In particular, Project Popcorn of the GPU Mode Discord aims to build “an LLM that can actually write good GPU code”. There is also interest in running GPU programming competitions for humans as a way to collect high quality training tokens for the LLM. We look forward to seeing how KernelBench can contribute to these initiatives.

Our vision for the longer term future is to simplify the generation of high-performance kernels that seamlessly adapt to diverse hardware architectures, enabling developers to achieve optimal performance with minimal effort. By accelerating the iteration cycles for machine learning model architecture design, we aim to empower researchers and practitioners to explore, prototype, and optimize ideas faster than ever.

In addition, the ability to generate kernels quickly is very important for adapting to new hardware architectures, which is often a barrier for adoptions of new computing platforms. We think KernelBench and related techniques could enable faster development cycles for new hardware by lowering the amount of human engineering effort to write new kernels for architecture.

Let’s make writing high-performance kernels far more accessible and convenient!

FAQ

Why not a compiler?

The current development cycle—from efficient implementations to generalizations to compiler integration—is lengthy. Efficient compilers often lag behind new GPU architectures by over two years: approximately one year for CUDA experts to develop optimized implementations and another year to generalize these optimizations into compilers. Traditional compilers excel in generating provably-correct, robust, and general-purpose solutions, making them indispensable for a wide range of applications. However, developing compilers remains a labor-intensive and time-consuming process.

Many design patterns and optimizations are reusable across GPU kernels –– fundamental principles such as overlapping, fusion, efficient memory access, and maximizing occupancy. Our approach seeks to complement traditional compilers by focusing on a different objective. Rather than striving for general-purpose, provably-correct compiler solutions, we aim to distill human intuition directly into specialized, high-performance code with correctness tested empirically. This enables the generation of code highly optimized for specific input shapes and computational patterns, a level of specialization that would otherwise require extensive pattern-matching rules and manual engineering in traditional compilers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Aaryan Singhal, AJ Root, Allen Nie, Anjiang Wei, Benjamin Spector, Bilal Khan, Bradley Brown, Dylan Patel, Genghan Zhang, Hieu Pham, Hugh Leather, John Yang, Jon Saad-Falcon, Jordan Juravsky, Mark Saroufim, Michael Zhang, Ryan Ehrlich, Sahan Paliskara, Sahil Jain, Shicheng (George) Liu, Simran Arora, Suhas Kotha, Vikram Sharma Mailthody, and Yangjun Ruan for insightful discussions and constructive feedback in shaping this work. We would also like to thank SWEBench for its inspiration and reference, which greatly contributed to the development of this work.

Citing

@misc{ouyang2025kernelbenchllmswriteefficient,

title={KernelBench: Can LLMs Write Efficient GPU Kernels?},

author={Anne Ouyang and Simon Guo and Simran Arora and Alex L. Zhang and William Hu and Christopher Ré and Azalia Mirhoseini},

year={2025},

eprint={2502.10517},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.LG},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.10517},

}