Today, we're releasing CodeMonkeys, a system designed to solve software engineering problems by scaling test-time compute.

CodeMonkeys scores 57.4% on SWE-bench Verified using Claude Sonnet 3.5.

Our candidate selection method can also be used to combine candidates from different sources. Selecting over an ensemble of edits from existing top SWE-bench Verified submissions obtains a score of 66.2%, outperforming the best member of the ensemble on its own and coming 5.5% below o3's reported score of 71.7%.

We are releasing:

- A paper that describes our method in more detail.

- The CodeMonkeys codebase. This includes scripts for reproducing all results from our paper and running CodeMonkeys on SWE-bench problems.

- All trajectories generated while solving SWE-bench problems. These trajectories contain all model outputs, candidate edits, test scripts, and execution traces generated while running CodeMonkeys on SWE-bench Verified.

- A careful accounting of the cost of running CodeMonkeys. Software engineering agents are expensive: running CodeMonkeys on SWE-bench Verified cost $2300 USD.

- A companion dataset containing complete Python codebase snapshots for all problems in SWE-bench Verified. This dataset makes it easier to work with SWE-bench by providing direct access to repository contents, without needing to clone and manage large Git repositories.

SWE-bench

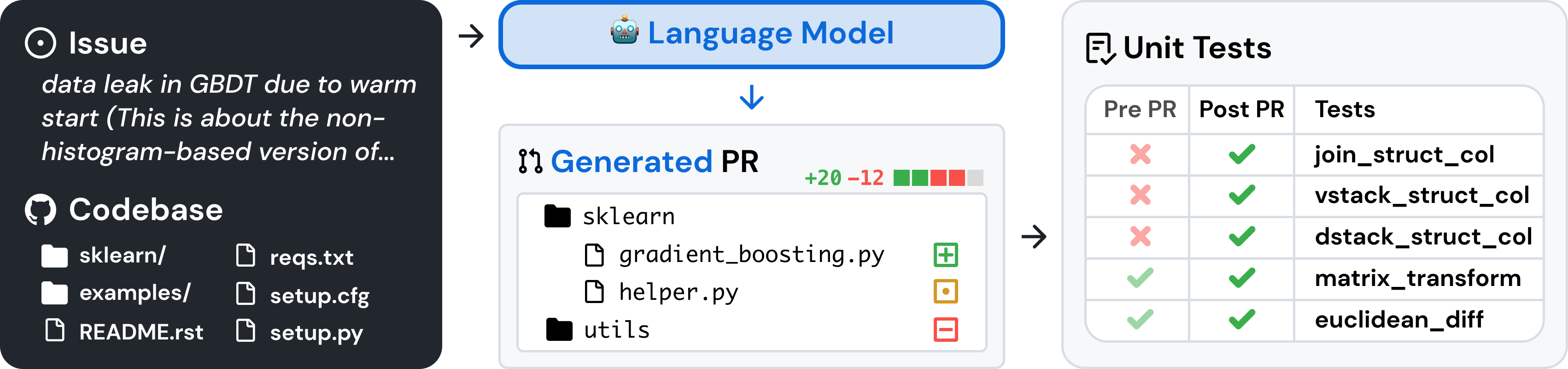

SWE-bench is a benchmark that measures how well AI systems can solve real-world GitHub issues. Each instance in SWE-bench consists of an issue from a popular open-source Python repository (like Django or SymPy) along with the complete codebase at the time the issue was reported.

Image from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06770.

To solve an instance, a system must appropriately edit the given codebase in order to resolve the corresponding issue. An edit can be automatically evaluated for correctness using a set of unit tests that are hidden from the system.

In this work, we've focused on SWE-bench Verified, a subset of SWE-bench where human annotators have filtered out low-quality instances (e.g. those with ambiguous issue descriptions).

Let's Talk About Monkeys

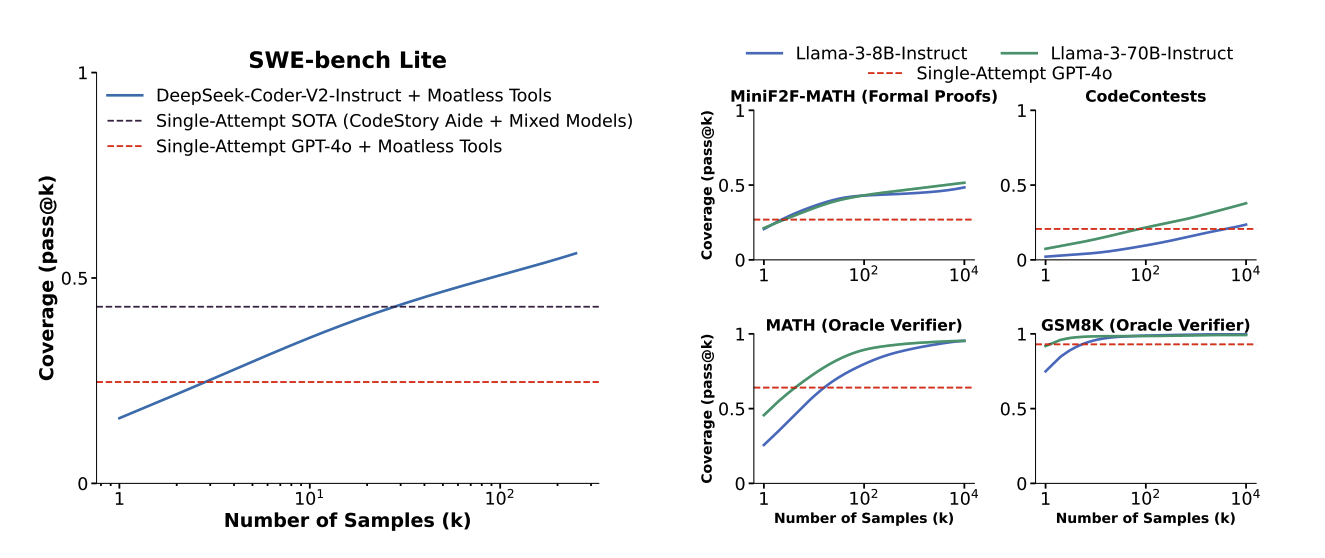

We began working on SWE-bench in our previous work, Large Language Monkeys. In that paper, we investigated the simple technique of using an LLM to sample many candidate solutions to a problem.

When solving SWE-bench instances (in addition to tasks from other datasets), we found that coverage, the fraction of instances that are solved by at least one sample, often increases log-linearly with the number of samples drawn.

More precisely, we found that the relationship between coverage and the number of samples can often be modeled using an exponentiated power law.

Image from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.21787.

These results showed clear potential for how we might use test-time compute to improve performance on SWE-bench; by investing more test-time compute in generating larger sample collections, we can steadily increase the probability that these collections contain correct solutions. However, achieving high coverage does not mean that a system can solve SWE-bench issues with a high success rate. Benefiting from coverage requires that a system can select a correct solution among its candidate generations.

Additionally, in Large Language Monkeys, we generated candidate edits by repeatedly sampling from an existing framework (Moatless Tools) which was designed for generating only a single edit.

This raised the question: how would we design a system differently if benefiting from test-time compute scaling was a primary consideration?

CodeMonkeys

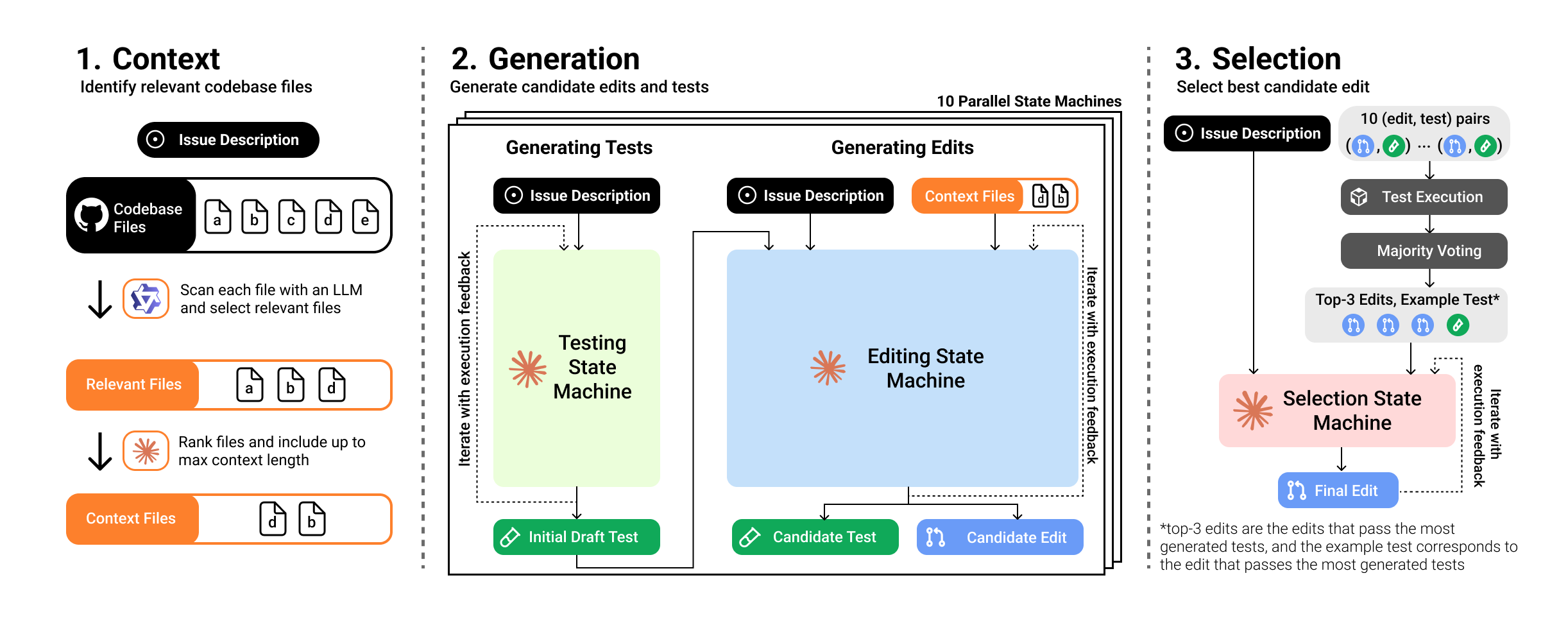

This question led us to build CodeMonkeys, a system designed to solve software engineering problems by scaling test-time compute. Similar to existing approaches like Agentless, we decomposed solving SWE-bench issues into 3 subtasks:

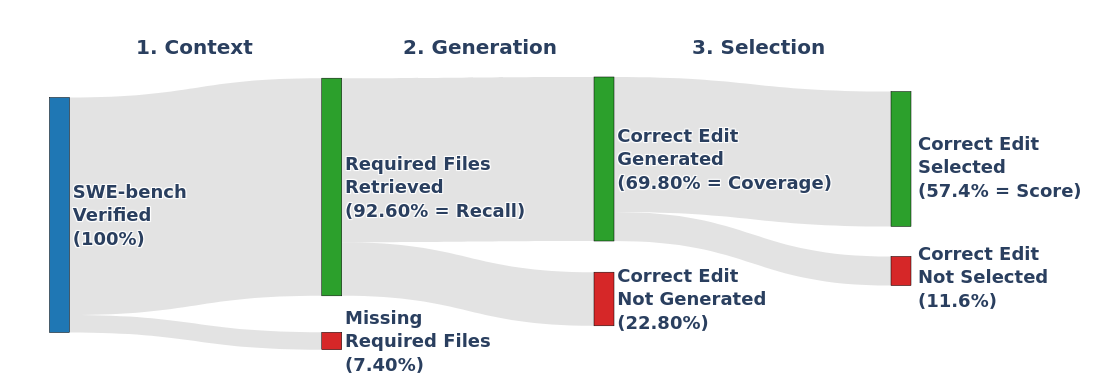

- Context: can we identify the codebase files that need to be edited and put them in the context window? We can measure outcome of this subtask with recall: the fraction of problems where all needed files have been identified.

- Generation: can we produce a correct codebase edit among any of our sampled candidates? We can measure this outcome of this subtask with coverage: the fraction of problems where at least one generated edit is correct.

- Selection: can we choose a correct codebase edit from our collection of candidates? After completing this subtask, we can measure our final score: the fraction of problems in the dataset that are resolved by the edit our system submits.

We measure the performance of our system on each subtask and describe our approach to each below:

Task 1: Context

Inputs: Issue Description, Entire Codebase (up to millions of tokens of context)

Outputs: Relevant Files (max of 120,000 tokens)

One of the key challenges when solving SWE-bench instances is managing the large volume of input context. Most SWE-bench codebases contain millions of tokens worth of context: this exceeds the context lengths of most available models. Further, it would be prohibitively expensive to process using frontier models.

We therefore need to filter the codebases down to fit in a smaller context window. Since we later sample multiple candidate edits for every SWE-bench instance, we can amortize this cost of context identification across all downstream samples.

We use a simple but effective approach to find relevant codebase files: we let a model (specifically, Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-Instruct) read every non-test Python file in the codebase in parallel, labelling each file as "relevant" or "not relevant". Then, we used Claude Sonnet-3.5 to rank the relevant files by importance. We include the top-ranked files in the context window, allowing up to 120,000 tokens of context.

Task 2: Generation

Inputs: Issue Description, Relevant Files

Outputs: Candidate (Edit, Test) Pairs

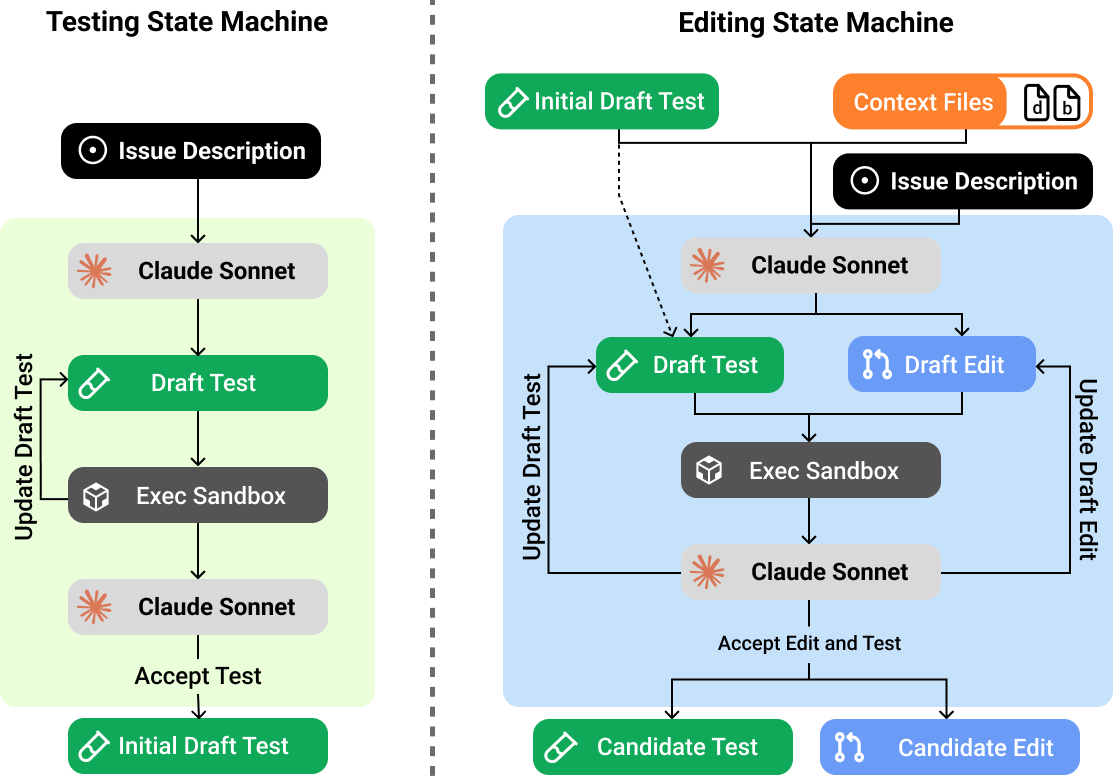

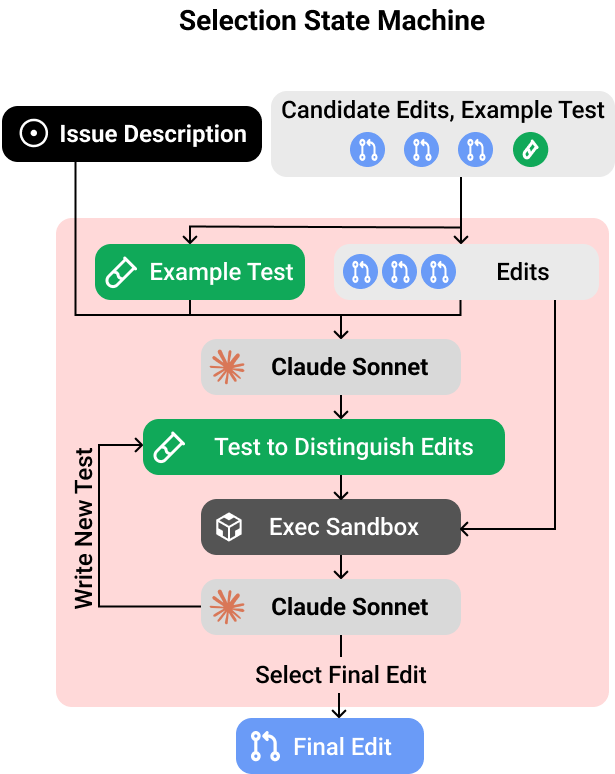

We decompose this stage of our system into two back-to-back state machines:

- An initial testing state machine which iterates on an initial draft of the test script.

- A follow-up editing state machine which iterates on a codebase edit. This state machine is seeded with the output of a testing state machine and can also revise the testing script as needed.

These state machines iteratively refine their outputs based on execution feedback. This provides two ways to scale test-time compute: we can increase the number of iterations per state machine ("serial scaling") or increase the number of independent state machines per problem ("parallel scaling"). In our experiments, we limit all state machines to eight iterations and sample 10 candidate (edit, test) pairs per SWE-bench instance.

Task 3: Selection

Inputs: Issue Description, Relevant Files, Candidate (Edit, Test) Pairs

Outputs: Final Codebase Edit

Finally, we select among the candidate solutions. We first use the model-generated tests to vote on solutions and narrow down our candidates to the top-3 edits that pass the most tests. Next, we run a dedicated selection state machine that can write additional tests to differentiate between these top candidates and eventually decide on one. Similar to the editing and testing state machines, this state machine can refine its tests based on execution feedback from previous iterations.

Cost Analysis

Across all stages, CodeMonkeys spends about 2300 USD when attempting all instances from SWE-bench Verified. We break down the cost by step below:

| Stage | Claude Sonnet-3.5 API Costs | Local Costs | Total Cost | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Output | Cache Read | Cache Write | Qwen-2.5 | USD (%) | |

| Relevance | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 334.02 | 334.02 (14.6%) |

| Ranking | 0.00 | 11.92 | 1.10 | 6.90 | 0.00 | 19.92 (0.9%) |

| Gen. tests | 10.60 | 295.15 | 21.60 | 112.64 | 0.00 | 439.99 (19.2%) |

| Gen. edits | 14.67 | 353.95 | 636.82 | 360.58 | 0.00 | 1366.02 (59.6%) |

| Selection | 0.52 | 51.12 | 15.17 | 65.14 | 0.00 | 131.95 (5.8%) |

| Total | 25.79 | 712.14 | 674.69 | 545.26 | 334.02 | 2291.90 (100.0%) |

A few interesting notes:

- Our context identification contributes only 15% to total costs - amortizing makes scanning the codebase with a (cheap) model feasible!

- Generating edits is the most expensive component (60% of costs), primarily due to cache read costs from including lots of codebase context in prompts.

- Selection contributes less than 10% to total costs while significantly improving final performance (see paper for ablations).

Barrel of Monkeys: Combining Solutions from Different Systems

| Method | Selection | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Barrel of Monkeys | Oracle (Coverage) | 80.8 |

| o3 | --- | 71.7 |

| CodeMonkeys | Oracle (Coverage) | 69.8 |

| Barrel of Monkeys | State Machine | 66.2 |

| Blackbox AI Agent | --- | 62.8 |

| CodeStory | --- | 62.2 |

| Learn-by-interact | --- | 60.2 |

| devlo | --- | 58.2 |

| CodeMonkeys | State Machine | 57.4 |

| Emergent E1 | --- | 57.2 |

| Gru | --- | 57.0 |

Our selection mechanism can also be used to combine candidate edits from heterogeneous sources. We demonstrate this by creating what we call the "Barrel of Monkeys" - an expanded pool of candidate edits that includes solutions from CodeMonkeys along with the submissions from the top-4 entries on the SWE-bench leaderboard as of January 15, 2025 (Blackbox AI Agent, CodeStory, Learn-by-interact, and devlo).

When we run our selection state machine over this expanded pool of candidate solutions, we achieve a score of 66.2%. This outperforms both CodeMonkeys on its own (57.4%) and the best member of the ensemble (Blackbox AI Agent at 62.8%), showing how our selection method can effectively identify correct solutions even when they come from different frameworks.

Limitations and Future Work

We see clear opportunities to improve our system further. Our file-level filtering still misses relevant files in 7.4% of cases and may struggle on less popular repositories that models don't already have background knowledge about. In generation, we currently don't use existing unit tests in a repository as a source of execution feedback, and we use a positive sampling temperature as our exclusive method of encouraging diversity across samples. Most notably, our selection method only recovers about half of the performance gap between random selection and oracle selection for CodeMonkeys, and less than half of the gap for the Barrel of Monkeys. Improvements to selection methods could potentially lead to large score increases, even if the underlying candidate generators are unchanged!

We look forward to continued progress in methods for scaling test-time compute and their applications to real-world software engineering tasks.

Citation

If our dataset, code, or paper was helpful to you, please consider citing:

@misc{ehrlich2025codemonkeys,

title={CodeMonkeys: Scaling Test-Time Compute for Software Engineering},

author={Ryan Ehrlich and Bradley Brown and Jordan Juravsky and Ronald Clark and Christopher Ré and Azalia Mirhoseini},

year={2025},

eprint={2501.14723},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.LG},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.14723},

}